Recently the camera market has seen the introduction of a new type of digital camera. Commonly referred to as an ILC (interchangeable lens compact) but also called "mirrorless" due to its most striking feature — the lack of a mirror box reflecting the image to an optical viewfinder. The latter has a long and storied history going back to the film era. The first such reflex I ever used was a 35mm Exacta, a somewhat cumbersome beast whose lack of features like an automatic diaphragm made it and similar cameras difficult and slow to use. But SLR models gradually improved and became the dominant design in 35mm cameras, far exceeding in popularity the older rangefinder type though the best brand of the latter, Leica, retained the loyalty of its users, at least those who could afford it. And Leica has been able to transition to the digital era.

But getting back to ILC or whatever you care to call it (there's a plethora of names for these things), virtually all the major camera makers offer models of this type with the notable exception of Canon, the largest manufacturer, at least as of this writing. However, I think we will see something from Canon in the near future.

I believe the first ILC camera was offered by a company that was not a traditional camera maker, Panasonic, with their Lumix DMC-G1. This was part of the Micro Four Thirds System jointly announced by Panasonic and Olympus in 2008 and utilizes the same sensor (7.3 x 12.98mm) as the regular Four Thirds system, smaller than the common APS-C size (somewhat variable but usually about 23.6 x 15.5mm) on most DSLR models but larger than that featured on compact (point-and-shoot) digital cameras. Like all ILC cameras they are smaller and lighter than DSLR models while featuring interchangeable lenses.

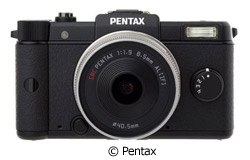

Speaking of size, the Pentax Q is probably the tiniest ILC (with a comparably tiny sensor as well — 5.76 x 4.29mm). It's so small that users with large hands might have some difficulty holding it. On the other hand, it's probably small enough to fit in a jacket pocket. Another offering from Pentax is the K-01, somewhat larger than the Q. However, it accepts virtually every lens Pentax has ever made. That's a noteworthy point because most of the mirrorless cameras require special lenses though they might accommodate other lenses with the proper adaptor.

Nikon also has two ILC models, the V1 and the J1. Sensor size is identical on both but the V1 sports an eye-level electronic viewfinder; the J1 only features the LCD screen on the back of the camera for framing your shots. Both Sony and Samsung have a strong presence in this niche market, each with several models.

Fujifilm recently announced their X-Pro1, a somewhat beefed-up version of the earlier X-100, a retro-looking camera that mimics the Leica M series in appearance but with a fixed f2 lens. Both sport a hybrid optical/electronic viewfinder but only the newer X-Pro1 offers interchangeable lenses.

Ricoh offers an interesting variation with its GXR mounts. These encompass the sensor, shutter, and other functions in an interchangeable module, one of which accepts Leica M lenses. For those who feel that the lens is most important part of any camera, this might be a major selling point for this offering from Ricoh, especially those who cannot afford a Leica M9. Then too, I suspect that users of the M9 would probably maintain that the M9 should not be grouped with the ILC cameras at all and not just because of its astronomical price (about $8000 US for the body alone). Its retro design is relatively unchanged since the introduction of the M3 in 1954, except of course the M9 features a digital sensor, not 35mm film. But the dimensions of the sensor, 24 x 36mm, usually referred to as "full-frame", are the same as the original 35mm film format. The M lenses are manual focus via a bright viewfinder/ rangefinder that is easy and quick to use and the quality of both the glass and other parts is outstanding, something we have always expected from Leica.

Ricoh offers an interesting variation with its GXR mounts. These encompass the sensor, shutter, and other functions in an interchangeable module, one of which accepts Leica M lenses. For those who feel that the lens is most important part of any camera, this might be a major selling point for this offering from Ricoh, especially those who cannot afford a Leica M9. Then too, I suspect that users of the M9 would probably maintain that the M9 should not be grouped with the ILC cameras at all and not just because of its astronomical price (about $8000 US for the body alone). Its retro design is relatively unchanged since the introduction of the M3 in 1954, except of course the M9 features a digital sensor, not 35mm film. But the dimensions of the sensor, 24 x 36mm, usually referred to as "full-frame", are the same as the original 35mm film format. The M lenses are manual focus via a bright viewfinder/ rangefinder that is easy and quick to use and the quality of both the glass and other parts is outstanding, something we have always expected from Leica.

Ok, I suspect that few readers of this article are considering a Leica M9 purchase so I won't discuss this jewel any further. But what about the real ILC cameras? Are they a viable alternative to a DSLR (or at least as a second camera body)? Well, that depends on what your needs are and whether you are willing to accept the undeniable limitations of ILC cameras.

Ok, I suspect that few readers of this article are considering a Leica M9 purchase so I won't discuss this jewel any further. But what about the real ILC cameras? Are they a viable alternative to a DSLR (or at least as a second camera body)? Well, that depends on what your needs are and whether you are willing to accept the undeniable limitations of ILC cameras.

Many of the ILC models lack eye-level viewfinders, making them similar to most present-day point-and-shoot cameras. A few offer electronic viewfinders as an added (and often expensive) accessory but the individual photographer must decide how important a viewfinder is. If you are not comfortable with holding the camera in your outstretched hands while framing the shot on the rear LCD screen, that fact alone will probably eliminate some of these models from consideration.

Another point relates to the autofocus system. Basically there are two types, contrast and phase. Most DSLR cameras feature the phase type (or a combination of the two) while virtually all point-and-shoot compacts have the contrast type. My advice — don't worry about it. Any decision regarding a camera purchase is likely to be determined by other features like size of the camera and how it feels in your hand as well as availability of lenses. And of course, cost.

The same goes for how many megapixels it comes with. But unless you plan to make huge prints from your digital captures, forget megapixels. Most models nowadays come equipped with at least 10MP, more than enough for most photo applications. More important is the size of the sensor in terms of the quality of the image. Generally speaking, the larger the sensor the better in terms of noise and detail. Most of the current ILC models come equipped with APS-C size sensors, making them comparable to DSLR cameras. By the way, I wrote an article about sensor size a few years ago for the NYIP website and the points I made then are still relevant today.

The same goes for how many megapixels it comes with. But unless you plan to make huge prints from your digital captures, forget megapixels. Most models nowadays come equipped with at least 10MP, more than enough for most photo applications. More important is the size of the sensor in terms of the quality of the image. Generally speaking, the larger the sensor the better in terms of noise and detail. Most of the current ILC models come equipped with APS-C size sensors, making them comparable to DSLR cameras. By the way, I wrote an article about sensor size a few years ago for the NYIP website and the points I made then are still relevant today.

In keeping with current DSLR models, most of the ILC cameras feature HD video capture though typically you have less control than you would with a dedicated camcorder. Still, it's nice to be able to capture motion and stills with the same camera. Besides, it's easier for the manufacturer to develop a video function in a camera that has no mirror flipping out of the way.

So why are we seeing this type of camera? And how come Nikon (still waiting on Canon) wasn't the first manufacturer into this market? One reviewer theorized that only companies that were not doing that well in DSLR sales and were looking for a less competitive niche decided to take a chance on the ILC. A new design requires considerable investment in R&D and maybe Nikon didn't want to risk taking away from their DSLR lineup, at least at first. Then too, some consumers are always looking for the latest thing. Or a camera that's smaller than a DSLR but with better image quality than their camera phone; small and compact like a point-and-shoot model but with interchangeable lenses.

I haven't seen any sales figures for ILC cameras but it appears that they are gaining in popularity, particularly amongst photo enthusiasts. But professional photographers need the performance that high-end DSLR cameras offer so that segment of the market will probably not embrace the ILC, at least at its current stage of development. On the other hand, people who take photos only with their camera phones will probably stick with that device. The technology for camera phones is also improving.

So should you buy an ILC and if so, which one? Here it gets complicated. There is an abundance of models (often from the same manufacturer) making any decision about purchases tricky indeed. Furthermore, the manufacturers are continually introducing new models with new and/or improved features. It's not an easy decision.

Getting back to the question I posed in the title of this article, are ILC cameras an alternative to the DSLR? Speaking for myself, I like the idea of a camera that's smaller and lighter than my DSLR, particularly in light of my limited mobility. But a bright optical viewfinder is a must for me (electronic types, while better than no viewfinder, are a poor substitute for the real thing). Anyway, I have an assistant to carry my gear nowadays (my wife) when I'm off on a photo project. The rest of the time I rely on the camera I always have with me — my phone.

Learn more about cameras and photography at NYIP Photography School.