This marks the beginning of a new www.nyip.edu series designed to introduce a new generation of photographers to the possibilities that exist making and working with black-and-white photographs.

We won't promise a new installment every month, but there will be regular chapters until we've covered the entire story. By the way, we are interested your suggestions and ideas for this series and we are open to proposals for installments to be written by our readers. Address your comments to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A Little History, Or, Who Killed Black-and-White the First Time Around?

Before there was color photography, there was black-and-white photography. Before national magazines were published with nothing but color photos, they used to run a color photo on the cover and a few color photos sprinkled through the rest of the magazine. Everything else was black-and-white.

Let's go way back: The shiny-and-dark image of the Daguerreotype was essentially, a black-and-white image. So too, the brown-and-white albumen print, the muted tones of the calotype and even the murky image of tintypes. Most of the history of the first hundred plus years of photography was etched in monochromatic tones– a photograph was a two-dimensional rendering of light and dark patches that created a black-and-white likeness of a real-world scene. Sometimes the dark portions were dark gray and black, other times dark brown and deep brown (sepia).

Even in the past fifty years, there have been lots of reasons to use black-and-white film. Early color film, processing and printing was expensive– much more expensive than black-and-white. Worse still, the quality of the images was often poor, particularly from low-cost labs used by amateurs. This was because the film wasn't so hot, the processing (except for very high-end magazine and advertising work) was shaky, and the volume wasn't there. For pros, only some jobs called for color images, the majority of photographs that were reproduced in print-even on television-were black and white. Color reproduction in magazines and books was usually poor right up to the 1970s or early 1980s. Sometimes it was downright lousy.

Today, we live in a full-color world. For photo viewers, even the color photos in newspapers are pretty good. Color images in magazines, books, television and– gasp!– the Internet too, are usually crisp and well-balanced.

For the makers of photographs, including the amateur photo enthusiast and even the family snapshot photographer, today's digital cameras produce color images that are better than ever. For the pro, almost every customer wants color, and the high-end digital cameras, quality processing and printing that is available allows us to produce photos that drip with eye-popping color. When that's appropriate. The result of this full-color media world is that today many photographers shoot everything in color.

Along the way to this full-color media world (starting around 1975-1980) there was an unintended consequence. The use of black-and-white film plummeted. There were many reasons: Manufacturers were offering better color film and processing at lower prices, while fewer and fewer commercial processors could do a good job processing black-and-white film. It even became hard to buy black-and-white film!

The result? The creation of black-and-white images dropped precipitously.

In little over a decade, black-and-white went from a basic photographic commodity to something that was a chore to purchase and tough to get processed. Lots of photographers, as we'll discuss in a moment, stuck with black-and-white in recent times and continue to produce fantastic work in that medium.

The people who have suffered are the ones who got excited about photography in the past ten to fifteen years. If you took up photography since say, 1985, there's a danger you haven't really had the fun of working with black-and-white film and getting good results. That's a real loss.

But it's an understandable situation. After all, if you have to work hard to buy black-and-white film, if you can't get someone else to process it, and if you can't easily buy the gear you would need to do the job yourself, then you would have to really be devoted to black-and-white images to learn how to make them and to keep making them. And, if you never learned how to do it in the first place, how can you keep the tradition alive?

But that was then. Now there's a different direction:

Black-and-white is back!

That's why it's time for you to get: Back to Black-and-white!

Black-and-white is back because it's part of the power of photography.

Black-and-white is back in print advertising. In today's saturated-color manipulated-image world, black-and-white feels real. To many, it looks fresh. This is true even though, as we'll discuss in this series, it's as easy to manipulate b/w images digitally as color ones.

Black-and-white is back because brides want to see black-and-white photos in their wedding albums.

Black-and-white is back because it's still a great way to learn about how film "sees" light. That's why good photo educators have never abandoned teaching beginners how to work with black-and-white film and images. That's why we still teach how to expose, process and print black-and-white film in the NYIP Complete Course in Professional Photography.

The bottom line? Black-and-white photography is back because it's beautiful.

As we mentioned, for pros and long-time serious photographers, black-and-white never left. The fine-art market in vintage photography has mushroomed in part because black-and-white silver halide images are long-lasting and resistant to fading. Street photographers who still admire the seminal work of Henri Cartier-Bresson expose countless rolls of b/w film in search of the “decisive moment.” For this type of imagery, color can be downright distracting.

Black-and-white is educational.

As we mentioned, black-and-white photography is a great way to learn about the photographic medium. Many would argue it is essential: Concepts of highlight and shadow detail, image contrast, film and exposure latitude and tonal range are all best understood by studying the black-and-white image. The traditional "wet" darkroom is still a place where the magic of the black-and-white image appearing in a tray of developer under the pale red glow of a safelight captivates people who are new to photography.

There's magic in the black-and-white darkroom. The color "wet" darkroom is a maze of chemicals (some quite harsh) and stringent temperature requirements. In truth, you have to be a glutton for punishment to process color in a home darkroom. For color, the computer's "electronic darkroom" excels. But the black-and-white home darkroom is a relaxing, informal place, where the rich black-and-white print can be pursued at a leisurely pace while listening to one's favorite music, sequestered from the light and the hustle and bustle of the "real" world.

In fact, if the black-and-white "wet" darkroom were to disappear, the world will be diminished.

The educational value of black-and-white film is not limited to making black-and-white images. In truth, color silver halide images are actually made out of three (or more) layers of black-and-white images that interact with color couplers to produce layers of color dye that when viewed together give the illusion of a full range of colors. Whether you're learning to control color film and prints, or even the different layers of a color image that has been scanned into a computer, the more you know about contrast, exposure latitude, and highlight and shadow areas of black-and-white images, the greater your mastery over color will be.

In short, even if you're accomplished and comfortable working in color, you'll derive great benefit from learning about black-and-white photography.

Black-and-white films.

Part One: Traditional Films

To choose from the full range of films for black-and-white, you'll have to visit a good camera store, either in your locality, by mail order, or on-line. Chances are, you won't find even a roll of black-and-white film, much less a decent selection at your local drug store or big discount store. This is one area where the specialty store shines.

When you get to a good store, you'll find a variety of great black-and-white films in a variety of speeds. The most common traditional b/w films are:

Kodak: BW 400CN, T-Max 100, T-Max 400, T-Max 3200, Plus-X (125), Tri-X (400),

Ilford: Pan F Plus (50), FP4 Plus (125), HP5 Plus (400), Delta 100 Pro, Delta 400 Pro, Delta 3200

Fuji Neopan 100 Acros, Neopan 400, Neopan 1600

In coming installments of Back to Black-and-White we'll discuss some of these films in detail. For now, just realize that the number that accompanies each film is its ISO, or speed. The higher the number, the "faster" the film, meaning that it is more sensitive to light.

We have some films on this list that are particular favorites, and a few that we don't like that much. That's a discussion for another installment of this series. You can get lots of details about each of these films by visiting the manufacturers' Websites. There are distinctly different approaches in site design at work, but with a little clicking here and there, you'll get lots of information at www.kodak.com, www.ilford.com, and www.fujifilm.com. The Kodak and Ilford sites offer technical sheets on each of these films in the form of downloadable PDF files. Cool.

For most users, we recommend using a 400-speed film, and for low light situations we suggest you try one of the 1600 or 3200-speed emulsions.

Other Black-and-White Film Stocks.

In addition to these traditional black-and-white films, there are some unusual film stocks that you might want to consider:

Kodak's BW400CN is a 400-speed black-and-white film that can be processed in conventional color negative chemistry, a process technically known as C-41. Traditionally, C-41 black-and-white films had one drawback — they're were not as stable as traditional black-and-white emulsions. But the benefit is that you can get decent processing at any photo store or one-hour lab.

We'll discuss C-41 films in detail in a later installment, but the benefit that the average one-hour lab can handle them is a big one. As we've mentioned, even the big processing outfits have been known to do a lousy job with black-and-white these days. We'll discuss your options for processing traditional film in a later installment, but if you have a lab that you love which does a great job with black-and-white, e-mail us with that information!

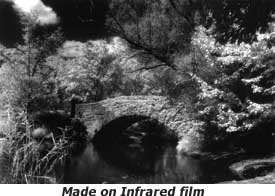

Other unusual stocks include Kodak's Infrared film, and Ilford’s SFX 200, which features an extended red range that gives an infrared "look" without the hassle. In addition, don't overlook the fact that Polaroid makes a number of black-and-white film stocks that can be useful for making certain types of images.

Despite the recent surge of interest in black-and-white, there have been recent casualties including Agfa's popular black-and-white film Scala. A few years back Ilford introduced a black-and-white single-use camera. Sadly, it too has been discontinued.

Black-and-white in your Computer.

While we're going to start our series with traditional film-based materials, bear in mind that you can convert any color photo to a black-and-white image in your computer. In computer language, such an image is called "grayscale," but don't let the tech-talk confuse you. We'll cover how to use the computer to make black-and-white images as well. Several digital cameras on the market also allow users to capture images as black-and-white. How's that for a comeback?

In Closing...

We hope this installment got you excited about black-and-white photography. Here's your assignment: Start looking for a film supplier and processor for your black-and-white work. If you have any suggestions for what you would like us to cover in this series, send them to “Back to Black-and-White”.